Looking Back, Looking Forward

The Palmer spent all day cruising back toward McMurdo Station to refuel. The ship travels at a steady 10 or 11 knots (about 12 mph), and we had about 300 miles to go. The scientists took this opportunity to review their data and decide where to visit during the second leg of our expedition.

Yesterday we had paid a second visit to an area called Station 16 that contained the strongest signal of Modified Circumpolar Deep Water the team had found so far. To understand this water in more detail, Bruce Huber put the mooring he had just recovered back into the water, and Dr. Josh Kohut’s team launched glider RU06.

The plan was for the glider to circle the mooring and provide supplementary information about the water conditions. Read on through the slideshow to see how the day turned out:

- As soon as we got to Station 16 the crew lowered the zodiac over the side and headed out to launch the glider (see Jan 21 post). The launch tests went well, but as the glider began its missions we learned that its compass was not working properly. This is partly because we’re so far south—farther south than the south magnetic pole. The Earth’s magnetic field here is more vertical than horizontal, so it pulls a compass needle more downward than southward.

- When he learned about the glider’s compass problem, Dr. Kohut reluctantly decided to abort the glider’s mission and the zodiac went back out to retrieve it. Here, marine technician Mark Harris makes a neat coil of rope and gets ready to throw it to a hand on the Palmer’s deck as we come alongside. Because the iron in the ship can distort compass readings, we can’t calibrate the compass while we’re aboard. And it’s too finicky a procedure to be done on a zodiac. Last time I saw Eli Hunter (the team’s glider wrangler), he was sketching out ways to land on an ice floe and calibrate it there.

- It was just three days ago that Bruce Huber spent 37 hours trying to rescue his mooring instruments (see Jan 25 post). Yesterday he and graduate student Julius Busecke led a team to put those instruments back in the water. They’ll stay here at Station 16 for the rest of our voyage and we’ll pick them up just before we go home. They’ll collect data on current speed and water temperature every 5 minutes between now and then, helping us understand where the MCDW is going.

- Preparing even a shallow-water mooring like this one is a complicated job that takes several hours. The ocean is deep and the instruments are heavy. If you drop something overboard before it’s firmly attached to the cable, it’s gone forever. This mooring will be attached to an anchor 400 meters (a quarter mile) below us. Floats at the surface will keep the line and its instruments tugged upright so each one measures at the proper depth. I noticed that after Bruce finished clamping each instrument to the cable, he put two zip ties on as safety fasteners. That’s what had saved his final instrument back on Jan 25.

- How do you safely put a half-ton, quarter-mile-long mooring and its delicate instruments into the water? You use that metal arch over the stern, called an A-frame. It’s 30 feet high and can hold 20 tons of weight. The A-frame can stand straight over the stern or lean out over the water. When it’s over the stern, the team can safely attach instruments. Then the A-frame leans out so the instruments can be lowered without danger of hitting the ship. Here, marine technician Jeremy Lucke uses hand signals to tell the A-frame and winch operators what to do. His closed fist means stop the winch.

- With anchor, cable, instruments, and surface floats already in the water, Julius tosses the final part of the mooring into the water. This is a ‘high-flyer’ buoy. It’s tall and skinny so it sits a little way above the surface. The metal triangles at the end reflect radar signals so that ships can see it from a long way away. There’s also a radio beacon that sends out a 2-second beep every 15 seconds at a specific frequency. It will help the ship’s captain find the mooring when we come back in about 16 days.

- At 2 p.m. today everyone gathered in the science conference room to review what we’ve learned so far and plan where to sample for the rest of the voyage. Each of the scientists on this trip is an expert in one field, but to understand what we’re finding they all had to consider results from outside their specialty. First they thought about what the CTD measurements told them about where MCDW was and where it might be going. Then they discussed iron measurements, how well the phytoplankton were growing, and what was happening to other nutrients that plants need. With so many topics involved the conversation was like a game of volleyball. As scientists threw their ideas into the air, one expert after another stepped in with specific knowledge to keep the discussion aloft.

- By 8 p.m. we were back in sight of Ross Island and about 50 miles north of McMurdo Station. The craggy slopes of Beaufort Island sit in front of the glaciers on Cape Bird, and there were icebergs in every direction. Soon we were passing little scraps of sea ice about 20 feet across and sitting only a few inches out of the water. Several thousand Adélie penguins breed on Beaufort Island, and many of the sea ice chunks had groups of a dozen or so penguins on them. The sun was out, the temperature was above freezing, and the penguins looked too hot.

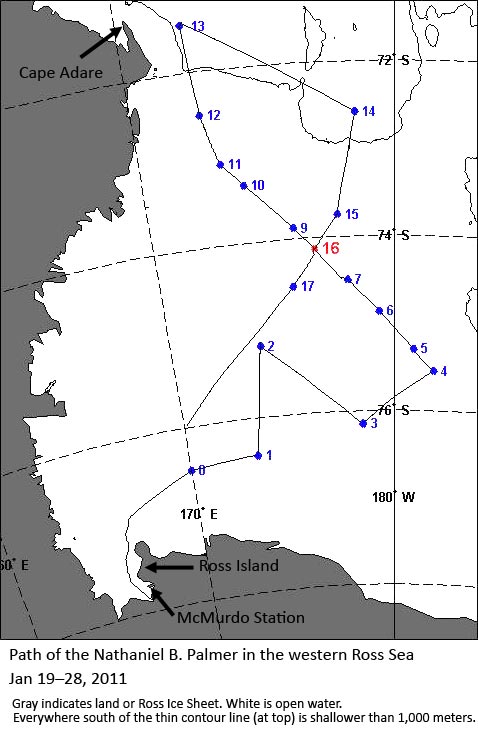

Today’s science meeting took two hours for the scientists to consider all the data and discuss the best way to spend their time for the rest of the cruise. So far, it seems that Modified Circumpolar Deep Water is carrying only a small boost of iron with it, but it may have been what caused a bloom that we found at station 7 (see map below). After we refuel, we’ll come back to station 16 to study MCDW more, and then do more sampling in the eastern Ross Sea.

We thought you might like a chance to review, too. So here’s a map of everywhere we’ve been since the expedition started. The points on the map show where we’ve taken water samples. The red point (16) is where Bruce and Julius just installed their mooring with its instruments. The track ends at about latitude 76° South, 170° East because that’s where we were when I wrote this.

Maybe this map can give you a sense of how difficult it is to understand the oceans. Even a small sea like the Ross Sea is big—it’s 450 miles from Cape Adare to McMurdo Station. Working as hard and fast as they could for 10 days straight, our science team has only been able to sample these 17 points. It’s as if you were trying to watch a game being played on the other side of a fence, and you could only see what was happening from between the fenceposts. After we refuel, we’ll work on adding a few more holes to that fence.

Many thanks to Eli Hunter for plotting the map of our ship track.

Read more in these related posts:

- ‘Glider Base, This is Zodiac’ (Jan 21)

- The Day That Lasted Two Days (Jan 25)

January 28, 2011

January 28, 2011

3 Responses to “Looking Back, Looking Forward”