Zodiac, Blizzard, Iceberg

It’s 7 a.m. and I’m just sitting down to write about yesterday. I can scarcely remember the emergency glider recovery that Dr. Josh Kohut and Eli Hunter put into motion at 2:30 a.m. yesterday morning. Then the clouds descended and the wind picked up, and the chief mate closed the decks, keeping us all inside for safety.

A brief calm spell took hold in the afternoon as the sky brightened and petrels and albatrosses gathered around our ship. People gathered at the bow, cameras raised, admiring an iceberg in the near distance.

Back in the Dry Lab, Dr. Kohut realized that Bruce Huber’s mooring was uncomfortably close to the massive berg. After narrowly getting Bruce’s instruments back during an all-nighter on Jan. 25, it seemed only fitting to pull another one tonight. As the wind regained its strength, the marine technicians readied their grapples, boathooks, coils of line, and winch cables for a soggy recovery. Read on through the slideshow to see the sights from our day:

- Third Mate Chris Peterson was at the helm of the Palmer when Eli got an unexpected message from glider RU07. Sensors inside the vacuum-sealed glider had detected some moisture, which could mean only one thing: a leak. We didn’t know how big the leak was, but we didn’t want to take any chances on the glider sinking. So Dr. Kohut asked Chris to take us straight to the glider’s last position for a rescue.

- For a day that included every kind of winter weather from sun to blizzard, we were lucky to have almost flat calm when we needed to recover RU07. When Eli got the glider back on his work bench, he was relieved to find that the leak was a small one—just a few drops, with no damage to the circuitboards. RU07 is finished for this expedition, but she’ll fly again. Dr. Kohut was satisfied. ‘We got a really nice section across Mawson Bank before we had to recover it, so I’m happy,’ he said.

- Just a few hours later the winds had whipped broad whitecaps onto the waves, and walls of spray battered the Palmer’s hull. Chief Mate Jace Eschete told everyone the decks were ‘secured,’ which means off limits, and asked everyone to refrain from using the washing machines while the ship was rolling. I thought that was a wise idea. As Chris looked out of this porthole, the horizon tilted and green waves crashed against the glass.

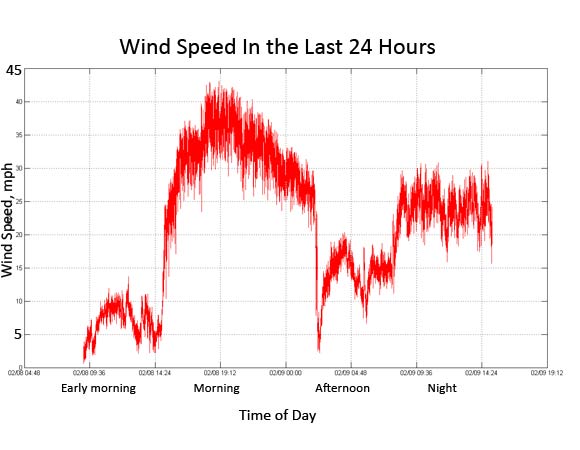

- All morning and into the afternoon the weather worsened. Snow squalls brought the visibility down to just the nearest half-dozen wave crests, and winds gusted to near 45 miles per hour (see graph below the slideshow). Seabirds like these two snow petrels barely seemed to notice. They ducked among the wave tops and settled calmly in between the whitecaps to dip at the water.

- With no one allowed on deck it was hard for many of the scientists to work. They trickled out of the Dry Lab to catch up on sleep, watch a movie, or play Settlers of Catan. So the weather took the opportunity to surprise us again. The wind went almost dead calm, the ocean surface smoothed, and the sun came out, complete with a halo of ice crystals you can just see above the cloud at center. But the lifeboat—four decks above the waterline—still carries evidence of stormy seas in the form of spray frozen to the hull.

- As the wind died, flying became harder work for the seabirds that followed us—they’re used to carving the wind on their narrow wings. This Antarctic Petrel took the opportunity to settle on our bow and preen its ruffled feathers. The black tube above its bill is a common feature in seabirds—a salt-excreting gland that enables them to drink the ocean’s salty water without getting dehydrated.

- You guessed it, the weather got cloudy again by suppertime. That isn’t the moon, it’s the sun disappearing behind a quilted blanket of low clouds. Next came snow.

- When we came back for a repeat visit to sampling station 8, we were surprised to find an iceberg nearly a mile wide just a couple of miles off our starboard bow. It looked about 70 feet high and had an arch carved in one end that we could see through. Squalls blew dusty ribbons of snow from its top, and waves crashed against its base, throwing spray 30 feet into the air. It was a magnificent sight, until we realized how close it was to Bruce Huber’s mooring (see Jan. 28 post). Can you see the yellow mooring float in the water at lower left?

- So by 2 a.m. this morning we were back in the bridge with Chris, the third mate. And we were headed for another recovery. On Chris’s radar screen, the Palmer is the white dot at the center. The plus sign is where Bruce’s mooring is, and the big, vaguely triangular blotch at left is the iceberg you saw in the last image. We calculated that it’s roughly half a square kilometer in size and probably 200 meters deep. That’s not deep enough to run aground on the seafloor here, so it might drift into Bruce’s mooring. I calculated it contains about 100 million tons of water (try to imagine the weight of 10 million minke whales)—not the sort of thing we want ramming into Bruce’s instruments.

- By 5:30 a.m. Captain Maghrabi had maneuvered the 300-foot ship snugly alongside the mooring’s ‘high-flyer’ buoy. Marine technician Alan Shaw snagged the mooring cable with a grappling hook and hauled it on board. Then he and Jeremy Lucke wrestled the first float onto the fantail and unhitched it. The wind had climbed to 30 mph and the windchill was about -5° Fahrenheit. A confetti of petrels spun past the stern and stalled out over the whitecaps. The fantail of the ship lived up to its name, as the stern first pitched into the air, then dipped down flush with the waves. Cold green water rolled across the deck. Jeremy, Alan, and the rest of the recovery team stuck to business despite the drenchings, and everything was aboard safely by 7 am.

Over the last 30 hours we’ve seen some stark reversals in the weather—the wind has gone from stiff to slack and back to blasting with barely a pause. But you don’t have to take my word for it: instruments on the ship keep track of wind speed continuously.

In fact, as we were marveling over the way the weather kept changing its mind, some of the scientists couldn’t contain their curiosity any longer and decided to graph the data:

Can you read this graph? It’s actually tracks our day pretty well. Wind speed is graphed on the vertical axis and time is on the horizontal axis. So as the day went on you can see that there was a really windy period followed by a weird, short calm spell. After that the wind built again.

Can you follow along with the events I described in the slide show and match them to the periods of wind and calm shown in this graph?

Many thanks to Eli Hunter for plotting the wind speeds.

Read more in the following posts:

- Looking Back, Looking Forward (Jan 28)

February 9, 2011

February 9, 2011

14 Responses to “Zodiac, Blizzard, Iceberg”