Brad, Ryan, and I left Punta Arenas, in the Southern tip of Chile, on New Year’s Eve. But before we left, T-Rex rubbed Magellan’s toe (a statue in the town square in Punta Arenas), which is a tradition thought to bring good weather during the crossing of the infamously rough Drake Passage. I love the murals painted in this little city and the Imperial Cormorant (black and white bird).

I don’t really think Magellan liked T-Rex much because we had a pretty rough crossing due to a low pressure storm front between Chile and Antarctica. Winds were blowing about 50-60 knots, and 20-foot waves were breaking over the bow of our research ship, the Laurence M. Gould (or LMG as we call it).

Watch this video of our ship moving through rough weather (filmed by Dr. Josh Kohut from Rutgers University, who is also down working at Palmer Station this season):

When the ship bounces like that, it is nearly impossible to do anything. If you lie down in your bunk, you have to secure yourself inside by stuffing things around you like life vests. But even then, you usually end up sailing up and hitting your head on the ceiling. Sitting in a swivel chair is bad news for your tummy, and even walking goes from weightless steps to feeling like you are carrying about 10 times your body weight in an instant. So the only thing that I can tolerate when the weather acts up is to sit on in the ship’s lounge chair and watch movies. So that is what we did until the weather cleared up.

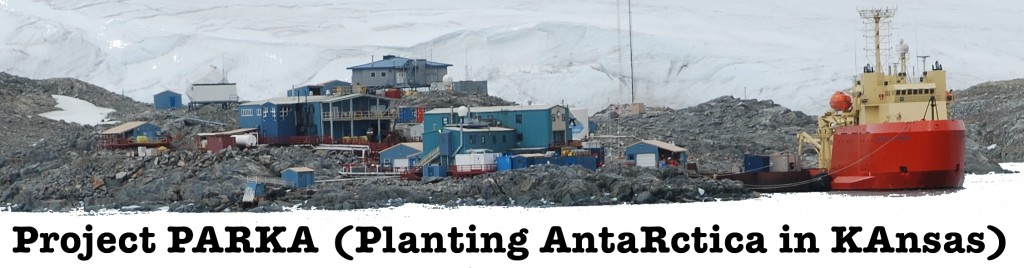

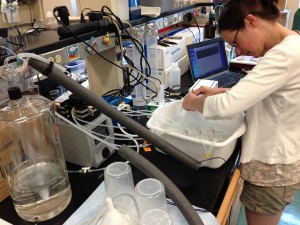

But we made it to Palmer Station on Sunday in one piece and met up with Abigail. The view from my Palmer bedroom window is pretty spectacular (see below). We have been very busy getting all of our equipment set up. This project is very multidisciplinary in that we will be focusing on many different aspects of krill biology and physiology as well as chemistry of the ocean and even krill blood. This is a picture of one of our labs – it’s pretty messy and full of equipment, but we are getting there!

The research ship that brought us to Palmer left on Tuesday morning for their 1-month cruise along the Antarctic Peninsula. This particular cruise has occurred every January since 1992 as part of a Long Term Ecological Research Project (LTER). Sampling of this type is very important to understand not only variability in ocean dynamics between years, but also is one of the only methods to see long term changes in the environment, such as those related to climate change. Read more about the Palmer LTER here: https://pal.lternet.edu/.

Their first order of business was to collect krill for our experiments. About an hour after they left the pier, the zooplankton group on board lowered a net into the water and towed it for a little while behind the ship at a low speed. This is the best way to collect large zooplankton for experiments.

Unfortunately, they brought the net up and there were NO krill! They did quite a few more net tows with no luck, then moved to a different location farther south and tried again. They were still not able to get any krill. There has been a very high amount of sea ice this year. What is likely happening is that because of all the ice this year, the normal biology of the Palmer Antarctic summer season is delayed. This is because sea ice can block the sunlight going into the ocean, and phytoplankton (microscopic plants of the ocean) need that light to grow. The phytoplankton that krill feed on just became abundant near the shore during the last week. Usually that happens a month or so earlier (November or December). So the krill are likely really far away from shore right now where there is little to no sea ice (offshore).

Due to our theory, chief scientist of the research ship, Dr. Oscar Schofield (Rutgers University), then decided to try to tow for krill offshore. And find they did! Lots of them! As soon as they collected the krill, they placed them carefully in buckets and brought them back to Palmer Station around 1:00 a.m. Wednesday morning. It was quite an operation – they had to crane them over to us.

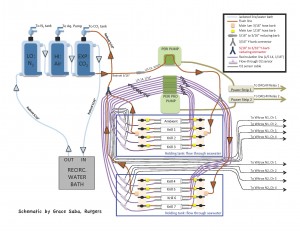

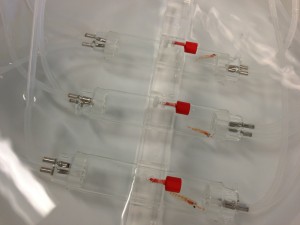

Once we brought them into their new home for the next month, we placed them into large aquariums with flow through seawater. We will begin experiments to look at the effects of enhanced carbon dioxide and temperature on their physiology in the next few days, so stay tuned!

Rutgers University undergraduate student, Ryan Fantasia, holding his first bucket of Antarctic krill.

Watch this video of the big krill swimming around…ENJOY!