Hi All,

Sorry it has been a while since our last blog post. We’ve had a super busy and productive season so far. There are a few posts coming your way to show you what we’ve been up to, both in work and free time. So heeeere we go…

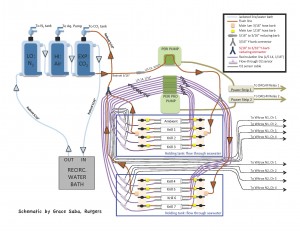

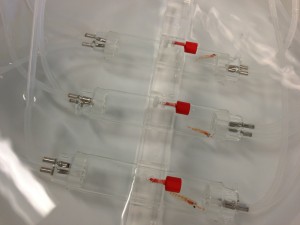

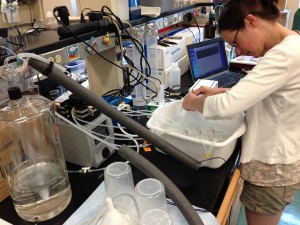

Once we got our krill from the Lawrence M. Gould, we decided to kick off the season with some short term experiments. The purpose of these is to see how krill physiology changes over a short time period (48 hours) when they’re exposed to high CO2 and/or high temperature. Some things that we measured included blood pH, cellular pH, and lactate.

Krill Blood

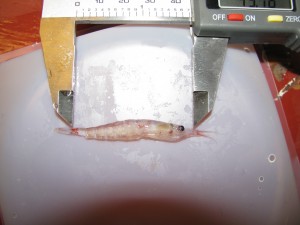

Krill have an open circulatory system, which means that there are no veins, arteries, or other blood vessels to carry around their juices. Like many other crustaceans, they also do not have any hemoglobin, the iron containing molecule in our blood that carries oxygen and gives it that nice red color. Instead, they use hemocyanin, a copper based molecule, which means the blood is clear-ish and difficult to find in these little guys. Brad and Abigail were able to find a nice large pool of it to take samples from.

Why these measurements?

One way that organisms can keep their machinery running smoothly is by moving things out of cells and into their blood, or vice versa. By measuring the cellular pH and blood pH, we can get an idea of how krill are moving around those little H+ ions (acidity).

Lactate works as an indicator of anaerobic respiration, the kind of metabolism that goes on when not enough oxygen can get to muscles in order to produce all of the energy they need. There are a couple of reasons organisms have to switch to this kind of respiration, but either is because they’re using oxygen more quickly, they’re have trouble getting oxygen to the muscles, or some combination of the two.

To measure lactate and cellular pH, their tails were chopped off and frozen to be analyzed back home. We do love our animals, but in order to study them, sometimes we have to do not-so-nice things. We are sorry, and we hope that their sacrifice will benefit the future of all krill-kind. No picture right here, in case it’s something you didn’t want to see, but feel free to click the link below if you do.

WARNING: GRAPHIC KRILL-HEAD CONTENT

Measuring all of these parameters is important, because if a krill’s metabolism is going to change under increasing ocean temperature and acidity, these results can help explain how this change comes about. It will be very interesting to see what we get here – and how it comes together to tell the story of how krill respond to a changing ocean.

Right now Abigail and I are conducting some repeats of this same experiment (which are always good to have in science) as well as a similar experiment where we see how the krill may react to the same conditions over a longer time period (21 days).