Prospecting off the deep end

The definition of “prospecting” is to search for mineral or metal deposits, or oil. While we are not on a hunt for substances to give us all an early retirement, we are in fact on the search for Iron and Sulfide-rich sediments, as well as trace-metals such as Germanium, found both in hypoxic conditions and off the Continental Shelf in the Gulf of Mexico. When Iron Oxide and Sulfide have the chance to combine, Iron sulfide is created with is commonly known as Pyrite or “Fool’s Good.” Unfortunately, the formation of Pyrite will never occur in the ocean because there is simply just too much Iron Oxide to be completely dissolved; no panning for souvenirs on this expedition. The stinky, sulfide-rich sediments are thought to contain the higher levels of iron though, which is one of the major focuses of this expedition.

The definition of “prospecting” is to search for mineral or metal deposits, or oil. While we are not on a hunt for substances to give us all an early retirement, we are in fact on the search for Iron and Sulfide-rich sediments, as well as trace-metals such as Germanium, found both in hypoxic conditions and off the Continental Shelf in the Gulf of Mexico. When Iron Oxide and Sulfide have the chance to combine, Iron sulfide is created with is commonly known as Pyrite or “Fool’s Good.” Unfortunately, the formation of Pyrite will never occur in the ocean because there is simply just too much Iron Oxide to be completely dissolved; no panning for souvenirs on this expedition. The stinky, sulfide-rich sediments are thought to contain the higher levels of iron though, which is one of the major focuses of this expedition.

So why Iron? Iron is considered to be not only a widely abundant element, but it also reacts to many other elements. As mentioned before, it can be considered as a Swiffer (mainly as Iron-oxide) to other elements and they cling to the iron as it moves through systems. In oxic waters, Iron Oxide will precipitate to the bottom of the water column, carrying with it many of the other present elements. As long as those waters remain oxygen-rich, the Iron and other elements such as Germanium will stay trapped within the soils. If the waters become hypoxic, however, the Iron Oxide will dissolve and be re-released into the system along with the other elements surrounding it. This is where the water samplings, core samples with pore water, and Lander samples come in to play: they are looking for that interface, that exchange happening at the surface to see at what levels and what other trace-metals are creating a flux due to the change in oxygen levels.

Still in the theme of prospecting, our day began with surveying the seafloor in roughly 1400m of water. Dr. Jim McManus, Dr. Will Berelson, and Bill Fanning were pouring over the depth finder regarding the terrain of the environment beneath us. They needed to find a location that was around these depths but consistently flat enough that the Lander could safely be deployed. They have also been taking into account water column pro in how they choose our spot to deploy. Through much searching and deliberation taking in all the facts, they determined a spot that all felt comfortable sending down and leaving the Lander at for almost 60 hours.

to find a location that was around these depths but consistently flat enough that the Lander could safely be deployed. They have also been taking into account water column pro in how they choose our spot to deploy. Through much searching and deliberation taking in all the facts, they determined a spot that all felt comfortable sending down and leaving the Lander at for almost 60 hours.

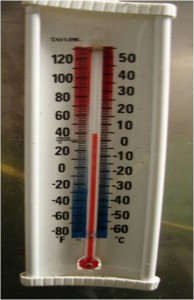

We are quickly approaching some of our deepest destinations for deployment while still staying in United States waters. Along with the pristine waters the middle of the Gulf harbors, comes the longer time for sending instruments to the bottom for collection. What originally could be done within a half an hour on the CTD, now can take upwards of an hour and a half to execute. The other quick reminder we got about the conditions of the deep sea was the consistent environmental factors, namely the temperature. As good as 10 C water may sound like it feels on a hot Gulf of Mexico afternoon, if you aren’t expecting it, it can be quite a shock.

April checking the pore water samples taken from the sediment, before we got into collecting the samples at 1400m.

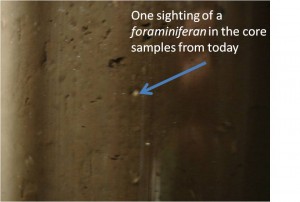

Jesse, Meghan, April, and Dr. Doug Hammond have also had a wardrobe change due to these depths. The refrigerated van where they have been processing the sediment samples has to be altered to match or be below the seafloor temperature, so the activity is suspended from when the samples are collected. You can see their smiles sink just a little as the CTD readings come back showing temperatures only 6 degrees away from freezing, when they know they have hours ahead of them in that room. With these core samples too, you can see the color change in sediment. The near-shore samples were more a muddy, gray color. While these are a lighter coffee-colored sort, with tiny white balls embedded in the sample. We were later told these are a type of foraminiferan, a type of protozooplankton found in these deep water samples.

too, you can see the color change in sediment. The near-shore samples were more a muddy, gray color. While these are a lighter coffee-colored sort, with tiny white balls embedded in the sample. We were later told these are a type of foraminiferan, a type of protozooplankton found in these deep water samples.

As soon as the last of the In-Situ pumps are pulled in tonight, around 10:30CMT (20:30GMT), we will be steaming farther south towards our next location of study. And though we will not be hauling in tons of precious metals, we are hoping for more consistent signs of trace-metals that can begin putting together the pieces of the puzzle regarding these elements and the role they have taken on in this unique environment.

August 8, 2011

August 8, 2011

Recent Comments