A sticky situation

Today, we awoke at our location for Station #5. The overnight steam brought us to our deepest depth yet, at 90m. Before we sent any instruments down near the bottom, we knew the sediment was very light weight because it was causing the depth finder to jump by 10 meters every second. The sediments were thick enough in the water near the bottom that the sensors were unable to pass through, but it made discerning true depth only somewhat tricky. By no means is this as deep as we will go. If you are following our expedition map or plotting our course along using latitude and longitude, you will see we are meandering slowly along the coast which mirrors the hypoxic plume, and will be turning towards the edge of the continental shelf of the Gulf area.

Today, we awoke at our location for Station #5. The overnight steam brought us to our deepest depth yet, at 90m. Before we sent any instruments down near the bottom, we knew the sediment was very light weight because it was causing the depth finder to jump by 10 meters every second. The sediments were thick enough in the water near the bottom that the sensors were unable to pass through, but it made discerning true depth only somewhat tricky. By no means is this as deep as we will go. If you are following our expedition map or plotting our course along using latitude and longitude, you will see we are meandering slowly along the coast which mirrors the hypoxic plume, and will be turning towards the edge of the continental shelf of the Gulf area.

Before breakfast again, Dr. Jim McManus, Bill Fanning, and I set out the CTD to determine the water’s characteristics at our new station. Though this depth still held hypoxic water between 70 and 90m below the surface waters, the samples at Station #4 reflect the highest levels of hypoxia so far; in fact the levels indicated were almost at zero at the previous station.

were almost at zero at the previous station.

The day’s routine then commenced with a CTD collection of new sea water from around 10m. The waters out here are absolutely stunning. Their inky, azurine depths hold water that is considered to be more pure than water produced by Milli-Q systems. Collecting fresh water for diluting solutions, or flushing tubes is not a problem when we are already checking the water chemistry with the CTD.

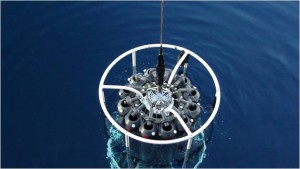

Each station will have at least one CTD, GO-Flo, In-Situ pump, Multi-core, and Lander deployment. Unless we need to move, or there is a need for more samples than one run can produce, the procedures remain the same. The exception this time, though, was with the Lander. Instead of deploying it with a series of buoys and an anchor, it is sent down to the bottom where it will not be disturbed for 24 hours. At the end of this time frame, the Lander will be triggered to release its weights and, with aid from floatation devices equipped with a beacon, rise to the surface. The Endeavor is staying in the area of the Lander, but not in a protective circling nature. Tomorrow, we all will be on the look-out for the buoys while the Captain will be using his radar to find the signal transmitted from the Lander.

I was fortunate enough to have some time to chat with Dr. Kanchan Maiti in his lab today. As mentioned in his profile, he is using the various collection techniques to sample for Polonium. Polonium, as you will learn more about as we post in our “Featured Elements” section, is a well-known radio-active element that has made news for its dangerous properties as well is its political affiliations. Dr. Maiti’s hypothesis in basic terms revolves around the knowledge that Polonium is known to leech from sediments in anoxic and hypoxic areas. He wants to begin taking the first steps through these explorations to see if there is enough coming out that it will make its way into the food chain, ultimately resulting in evidence of bioaccumulation in the flora and fauna found in this, and other, ecosystems.

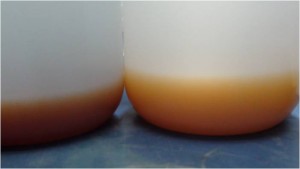

elemental Swiffer, where it moves through an environment and causes many different elements to cling to it. As time passes, the Iron precipitates to the bottom with, hopefully, the Polonium and other elements in the sample. Then Dr. Maiti can collect the condensed sample from the 5 gallon containers and slowly transfer them to the 1L bottles. At the end of this trip, he will have many smaller, more manageable samples to take back with him for analysis at LSU. Each of those 1L bottles is one sample; it all comes down to that little bit, after beginning with a rosette of twelve 12L tubes sent to the bottom of the Gulf on the continental shelf.

August 7, 2011

August 7, 2011

Recent Comments